News and Updates

Money Management and the Aging Brain

Money Management and the Aging Brain

September 22, 2015 – by Tobie Stanger • consumerreports.org

We’re all apt to get a bit fuzzier at money math as we age. The decline of financial skills—counting money, understanding debt and loans, paying bills, having the judgment to make prudent financial decisions—may be an early marker of something more: mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease.

In normal aging, cognitive abilities involving speed—learning new material, recalling facts, shifting attention—slow down, notes Bennett Blum, a forensic and geriatric psychiatrist in Tucson, Ariz. Other abilities, associated with language and reasoning, improve. How an individual is affected depends on genetics, health, environment, physical activity, and other factors. And the decline may not be noticed for years if a senior functions well otherwise. “Someone who’s not with the elder often won’t even recognize it or might chalk it up to eccentricity,” he says.

Only when a senior gets gulled into an unnecessary reverse mortgage or makes a bad investment decision—say, buying “gold” coins of questionable value—does the change make itself known. Stressful situations—often imposed by pushy telemarketers and outright scammers—also can highlight the impairment.

Declining cognition and dementia are blamed for seniors’ susceptibility to scams, but those with intact cognition also can get snookered, possibly because of other pressures that make them more vulnerable. Loss of a relative, family discord, financial worries, or an overdependence on another person—all can contribute, says Susan Bernatz, a forensic neuropsychologist in Marina Del Rey, Calif. “I’ve seen many cases involving people with full mental capacity whose trust and dependency were exploited for another person’s financial gain,” she says.

Notably, cognitive decline affects financial decision-making differently among personality types. A study published in 2014 by researchers from DePaul University and Rush University Medical Center found that seniors who have an overinflated faith in their financial abilities could be more vulnerable than others to money scams. As their cognition wanes, the risk increases. What’s more, the report said, getting stung once might not be enough to keep some overconfident types from being defrauded again.

Read the article here:

http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/consumer-protection/money-management-and-the-aging-brain

Tips for Alzheimer's Caregivers: Preventing Burnout

Tips for Alzheimer's Caregivers: Preventing Burnout

July 27, 2015 – by Eric J. Hall • huffingtonpost.com

Blend Images - Dave and Les Jacobs via Getty Images

Summer is notoriously one of the busiest times of the year. During the summer it seems as though we all have more trips, more weddings, more responsibilities and less time to get everything done. It can be easy to get overwhelmed during the summer and feel burned out with all of the extra activities. This is even more of an issue for Alzheimer's caregivers who have a huge load of extra responsibility piled on their everyday tasks.

Many Alzheimer's caregivers become so invested in the demanding job of taking care of an individual with dementia that they find themselves at risk of burning out. Caring for someone with this disease can be stressful and overwhelming and this can lead to burnout, and in many cases serious issues such as depression.

Here are some of the most common signs that you may be experiencing, or close to experiencing, burnout.

- Overwhelming feelings of frustration with the person you are caring for

- A new found lack of patience with the individual you are caring for

- Fatigue

- Feeling overwhelmed or overly emotionally

- Having trouble concentrating

- Feeling resentful towards others

- Developing new or worsening health issues

- Possessing a feeling that life will never get easier or better

- Experiencing changes in sleep or appetite

- Feeling a need to abuse medication or alcohol

- Believing that life is never going to get easier or better

These are all indications that you may be burning out. This can be a confusing time for any caregiver. On one hand you love the person you are caring for, but on the other, you are overwhelmed with these feelings in a way that can make you feel negative towards your loved one.

The first thing you need to do is to go easy on yourself. Just because you get frustrated, it doesn't mean that you are a bad caregiver or that you don't care. It is completely normal to get frustrated with the person you are caring for, and this is OK. Do not try to be the perfect caregiver, just do what you can and take everything one day at a time.

One of the best ways that you can help prevent burnout is to surround yourself with people. Having a strong network of family and friends can help you get the support that you need. You can also reach out to your doctor for ongoing support as you deal with the struggles and frustrations with being a caregiver. The more proactive you are and the more you attempt to surround yourself with those who can help you, the better off you will be.

Many times caregivers feel as though they must neglect their own needs, simply because they are so busy or feel as though they must only focus on the needs of the individual they are caring for. This is a very common sign of burnout, and something that can cause extreme stress. If you do not care for yourself, then you cannot be the best caregiver possible, so make certain you are always taking time to care for your own needs.

When someone offers you help with your caregiver responsibilities, make sure that you say "yes." It is OK to accept help from time to time, you don't always have to be the only one caring for your loved one and you don't always have to control everything. If you take the time to give small tasks to others then you will start feeling less stress and can prevent burnout. If you take it upon yourself to start proactively preventing stress, then you can prevent issues with burnout from taking over so you can be the best caregiver possible for your loved one.

Read the article here:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/eric-j-hall/tips-for-alzheimers-caregivers-preventing-burnout_b_7867292.html

White House Aging Conference: New Directions--Big Challenges

White House Aging Conference: New Directions--Big Challenges

Aug 03, 2015 — by Bruce Chernof, MD • newamericamedia.org

Photo: President Obama photographed with a group of White Conference on Aging dignitaries.

Article author Dr. Bruce Chernof is on the president’s right.

WASHINGTON, D.C. -- The White House held its sixth Conference on Aging, earlier this month, and this once-a-decade program took an entirely different approach to the discussion of what it means to age in America.

Since the first conference in 1961, the United States has changed in dramatic ways, and this year’s conference challenged participants to think more broadly about aging, to reimagine today’s longer lives in ways that better represent the experiences and needs of Americans.

Three Successes

For me, this year’s conference succeeded in three important ways.

First, President Obama attended and spoke forcefully on the issues at hand, acknowledging America as an aging and vibrant nation.

His remarks are critical given that aging as a personal, family, community and societal issue gets scant attention compared to other domestic matters. Bringing the presidential bully pulpit to bear on broader questions of how we wish to age; what we want the support system to look like; and how one’s dignity, respect and choice should be honored when having needs — as most of us will — is the White House’s appropriate and vital role.

Second, the conference theme provided leadership on setting a vision to transform how Americans can talk respectably about vulnerable aging and the need for daily supports.

Speakers broke from well-worn, unproductive narratives of aging (aging = being sick, poor, and alone; caregiving = burden; aging policy = safety net programs). These themes have tended to frame issues of vulnerable aging as someone else’s problem -- not concerns in which all American have a stake -- therefore excluding them from serious public discourse.

Instead, the conference reshaped what it means to age with needs in creative ways. How can we learn from the sharing economy to support the needs of older adults living in the community and their caregivers? How can the banking industry play a role in identifying older customers’ early cognitive impairment and protect them against elder abuse by spotting suspicious activity in their accounts?

How can technology enable safer, more connected environments so older adults can live as they choose? These discussions are relevant for all economic strata.

Third, the conference moved beyond Washington, D.C.’s insider debates among policy aficionados by engaging local communities from grassroots to grass-tops champions. Conference leaders and cabinet secretaries facilitated listening sessions across the country, starting in Sacramento last September at The SCAN Foundation’s Long-Term Services and Supports Summit and continuing throughout 2015.

Conference staff developed four public policy briefing papers [http://tinyurl.com/qdce69a] to inform those tuning into the day’s program around the country in order to spark public comment onsite and online. Live streaming and an active social media presence connected 700 community watch parties to the conference, with the hashtag #WHCOA reaching #3 on Twitter’s trending list that day.

What Was Missing?

So what was missing? With all the talk about building retirement security, there was no mention of the largest and most unpredictable factor that erodes it: the cost of long-term care (LTC).

A federal report released after the conference shows that half of Americans who reach age 65 will have severe functional needs in their life with an average cost of $138,000 overall. Families have few tools to plan for this economic shock due to the broken LTC insurance market. This is a profoundly important issue for racial and ethnic communities.

As the country ages, older adults will be more diverse, have fewer resources and likely fewer children in their families available to provide the necessary care.

We need to build a set of forward-looking solutions that account for these realities. This includes strengthening and modernizing both Medicare and Medicaid -- programs now being celebrated for their 50th anniversaries -- to better meet the needs of vulnerable people to live successfully in the communities of their choice.

It also means seeing LTC needs as part of a larger picture of well-being as we age, which requires new thinking about economic security.

The White House conference made a point to highlight the role that the private sector might play in bringing new innovation to aging services. This is a very important question for ethnic and racial communities.

Technology can be an incredibly effective tool in overcoming language barriers and increasing connectivity, but it needs to be planned for and built intentionally.

Furthermore, we need to move beyond a usual “digital divide” discussion and start thinking about the next wave of technology in our lives — the internet of things.

In the next decade, almost every home appliance or device will be able to connect and communicate through the Internet. Pillboxes will know someone is out of medications and automatically order them. Refrigerators will know if the milk has expired or if its door hasn’t opened in the last 24 hours, possibly prompting a call to see if a senior is all right.

The examples are myriad. The question is will everyone have access to this kind of technologic support in their homes?

Furthering the Dialogue

Beyond the conference, the administration should further the dialogue on aging across people and systems.

Although direction and resources originate from federal efforts, services are delivered locally with much that states and localities can do to better the lives of older adults and families. The private sector’s key role continues to be creating innovation for wider adoption; this must include ethnic and immigrant communities.

America is changing through population aging. We are reshaping family, work, retirement and societal engagement, which will fundamentally alter the landscape starting with Boomers and then Gen Xers, Millennials--and those beyond.

We will be a far more diverse country over the next few decades and America is just beginning to embrace this new reality. It is time that social and economic structures evolve to better meet the needs of vulnerable elders in every community.

Read the article here:

http://newamericamedia.org/2015/08/white-house-aging-conference-new-directions--big-challenges.php

Elderly Drivers Are More Dangerous Than You Might Think

Elderly Drivers Are More Dangerous Than You Might Think

July 9, 2015 — by Collin Woodard • cheetsheet.com

Source: Thinkstock

Caring.com, a popular website that bills itself as an “online destination for caregivers seeking information and support as they care for aging parents, spouses, and other loved ones,” has released the results of a study on senior driving behavior, and the results are shocking.

Based on the results of a study conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates International, it appears that elderly drivers were responsible for as many as 14 million traffic incidents in the past 12 months. Despite the frequency of elderly drivers causing crashes, most other people were concerned more with distracted drivers, teen drivers, and drunk drivers.

Interestingly, those who are 65 and over are most likely to consider elderly drivers more of a danger on the road than drunk drivers. Even though they’re more aware than any other group that continuing to drive becomes increasingly hazardous as they age, it’s not always clear to either their families or them when that time has come.

To dig a little deeper, I talked with Caring.com’s CEO Andy Cohen about the results of the study. Over the phone, Cohen said that even he was surprised at how high the accident rate was for senior citizens. The study included incidents that occurred without injury, but even so, 14 million per year is a very high number.

One issue he highlighted is that doctors rarely want to get involved in the decision making process, potentially to prevent legal liability issues, so even though 21% of elderly drivers would like their doctors to tell them when it’s time to give up the keys, the decision almost always falls on family members to make the decision.

Laws that govern how often senior citizens need to to be retested in order to keep their drivers licenses also vary widely from state to state. Some require it every year, while others only require it every five years. Only 10% of seniors want the government telling them when they have to give up the keys, but driving ability can drop drastically in just a few years.

“It’s a large growing issue, and it really falls to the adult children to deal with it because doctors and law enforcement don’t want to deal with it,” said Cohen.

Source: Thinkstock

He also believes that modern safety technology can help elderly drivers hold onto their keys longer. They may not necessarily trust the new features they’ve never used before, but for a lot of older drivers, if they have to choose between upgrading their car or giving up driving all together, they’ll choose the new car. It isn’t wise to encourage someone who truly shouldn’t be driving to keep doing so even if they have a brand new car, but having that safety net in place can definitely prolong the amount of time it’s safe for a lot of people to drive.

When adult children feel like it’s gotten to the point that they have to have the talk with their parents about giving up the keys for good, it’s important that they know it’s normal to be uncomfortable bringing it up. In a past Caring.com and National Safety Council survey, 40% of adults said they were more comfortable talking about funeral arrangements with their parents than they were driving.

The best thing to do, though, is to present concerns in a loving and thoughtful way and encourage them to make the decision to stop driving for themselves. “Driving is often associated with independence and freedom, which is why many senior citizens are reluctant to give up their car keys,” said Cohen.

If you can acknowledge their need for independence and develop a plan to make sure they don’t feel abandoned or trapped in their own home, elderly drivers are much more likely to voluntarily give up their keys. Cohen pointed out that many states offer free ride share options for senior citizens that can help them get out of the house without needing to drive.

Modern ride sharing services like Uber can also help senior citizens get around more easily and cheaply than calling for a cab. Cohen did say, though, that even if they can afford to have a car take them somewhere they want to go, a lot of elderly people may still resist doing so because they want to save their money. If that’s the case, sending a pre-paid ride to take them to an activity you know they’ll enjoy can work well.

Talking to elderly parents about driving is definitely intimidating, but the consequences of not bringing it up are serious. Elderly drivers might not get as much attention as distracted drivers or drunk drivers, but they’re certainly still dangerous. Having a hard conversation with your parents is never fun, but for their sake and for the sake of the other people they may injure, it’s worth it.

Read the article here:

http://www.cheatsheet.com/automobiles/elderly-drivers-are-more-dangerous-than-you-might-think.html/?a=viewall#ixzz3gC3vlrxh

Who Will Care for America's Seniors?

Who Will Care for America's Seniors?

April 27, 2015 — by Alana Semuels • theatlantic.com

Lynne Sladky / AP

Being a home-health aide is a lonely, difficult job, and the pay is miserable. But the country needs to find millions more people to do it.

My grandfather broke his hip at age 87. At the time, he lived with my grandmother in western Massachusetts in a beautiful house they’d built themselves abutting a farm. At 88, she was as “with it” as someone decades her junior, and she was determined to help him continue to live at home, where he could listen to classical music in his sunny study, or gaze at the sheep that sometimes grazed outside his window.

He went to a nursing home for short-term rehab right after the accident, and it was nightmarish, she told me. He was trapped in a room with patients who would be there for the rest of their lives, which depressed him. Nurses gave him his medication on an erratic schedule, not necessarily prioritizing his health. My grandmother decided he would do better at home.

It didn’t seem like it would be too hard. They’d added a downstairs bedroom and bathroom a few years back, so he wouldn’t have to go up stairs. And she was still mobile, and could cook for him and spend time with him and set reminders on her iPad for when it was time for him to take his medication. She had family and friends nearby, who could spell her from caretaker duties from time to time. Plus, they had paid tens of thousands of dollars for long-term care insurance, which would pay for a home-care aide to come and help them when needed.

But finding help proved nearly impossible. The long-term-care insurer would only work with two agencies in the area, and they were swamped with demands. Often my grandmother would call and request help and no one could come. The agencies' staff tended not to live in Amherst, a college town with a population of 35,000, and would have to come from other towns, driving a long way from one client to another.

In western Massachusetts, where unemployment is low and full-time steady work isn't too hard to find, working a few hours a day for different clients for low pay didn’t appeal to many people. My grandmother didn’t need someone to be at the house all day. She mostly needed help getting my grandfather out of bed in the morning—he was a tall man, and was suffering from Parkinson’s disease, which meant his body sometimes wouldn’t obey his mind— into and out of the shower, and out of his wheelchair into bed at night. Though the agency charged $25 an hour, the workers only got about $15, which was, in fact, high for the field. The agency set a minimum visit of two hours, more than my grandparents needed at any one time.

Eventually, my grandmother stopped depending on the agencies, and, through a friend of a friend, found a Ph.D. student from Kenya named John. John was vastly overqualified for the job, but he was looking for a little extra cash, so he came to help my grandfather get out of bed in the morning and back into it at night, all while juggling his studies and his small family, who had moved with him to Amherst. John quickly became adept at the tasks of a home health aide, and he and my grandfather shared a bond, talking about Kenya and public health and academia. John was there when my grandfather suddenly died two years ago. My grandmother gave a donation to his village in his name as thanks for his help. She’s never heard from him again.

My grandparents lived in Amherst for 50 years. They didn’t want to move as they got older, and they weren’t unusual in this. Nearly 90 percent of seniors want to stay in their own homes as they age, according to AARP. Sometimes, it’s not a choice: Government programs such as Medicaid, in an effort to save money, are shifting spending away from institutional settings toward home and community-based care.

At the same time, the number of seniors is growing. In 2010, one-sixth of the adult U.S. population was older than 65; by 2030, about one-fourth will be.

“What’s coming down the pipeline—it’s a demographic tsunami,” Lawrence Force, director of the Center on Aging and Policy at Mount Saint Mary College, told me.

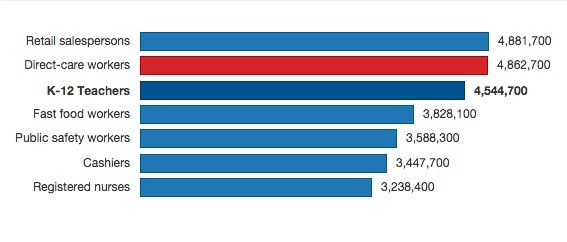

But the resources to help seniors stay at home are shrinking. Many seniors are finding that their boomer children are staying in the workforce longer than they did, and are unable to care for them. Demand for direct-care workers is expected to grow 37 percent between 2012 and 2022. Demand for personal care aides alone—the entry-level workers in the field—will grow 49 percent. There are currently 3.5 million direct-care workers in the country, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Seven years from now, there will be 1.3 million more.

More and more people are going to face the same problem my grandparents faced. They may have saved lots of money, or bought into long-term care insurance, and they might have all their affairs in order. But that doesn’t mean they’re going to be able to find someone to take care of them when they stay at home. About 20 percent of the elderly live in non-metropolitan designated areas, according to the National Rural Health Association, which makes it harder for them to find helpers nearby.

Money is also a problem: Medicaid reimbursement rates govern wages in the industry, but states have kept reimbursements flat as they struggle with budget issues, said Abby Marquand, Director of Policy Research with the Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute, or PHI. It's part of the Catch-22 of the home-care aide field—policymakers want to help people age at home because it's cheaper than a nursing home, but agencies argue that it won't be cheaper anymore if they raise wages and pay for overtime.

The resulting dearth of workers who stick with the field is creating headaches for the agencies charged with caring for the elderly at home.

“We can’t find quality staff—I can hire 10 people and keep two,” Jacqui Carson, the chief executive of Sanborn Place Home Care and Day Services, a residence for low-income seniors in the Boston area that also provides home care, told me. “This job doesn’t pay, because reimbursements are low.”

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute

Carson’s organization also runs a home-care service, and during the snowstorms this winter, staff couldn’t get to patients' homes, and, even if they could, they couldn’t afford child care for their kids who were home with snowdays. So Carson shoveled her way into seniors’ houses herself.

To get more dedicated people in the field, though, something needs to change, she said.

“I would hope that somewhere along the way, people understand that our CNAs are as needed as our engineers,” she said.

Part of the problem is the very nature of the jobs. On average, home care aides work 34 hours a week, and make an average of $17,000 a year. One in four live in households below the federal poverty line, and one in three doesn’t have health care because their employer doesn't offer it or because they can't afford it. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the field has a high rate of turnover—some estimates put it as high as 60 percent.

Of the ten occupations that added the most new jobs in 2012, personal-care aides earned less than all except for fast-food workers, according to the Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute.

“Some would call it a dead end job,” said Deane Beebe, a spokeswoman for the Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute, or PHI. “These are very hard jobs. They’re very physically taxing—they have one of the highest injury rates of any occupation—and they’re very emotionally taxing: It's intimate work; it’s isolating work.”

There are efforts under way to make these jobs more appealing to workers, but they haven’t gained much traction yet.

For one thing, home care aides aren’t covered included under the Fair Labor Standards Act, which means they’re not subject to overtime pay or minimum wage requirements. The Obama Administration extended the FLSA in 2013 to cover home-care workers, but a federal judge struck down that rule in January of this year. The Department of Labor is appealing the ruling, which applies to home care aides and personal care assistants, but not nursing assistants.

At the core of the debate is whether America’s 1.7 million home-care aides are “elder sitters,” and are thus, like babysitters, excluded from labor rules. Congress expanded FLSA coverage to domestic service workers in 1974, but exempted babysitters and companions for the aged and infirm. In his decision, the federal judge wrote that Congress would have to change the law in order to include home care aides under the labor standards—it currently likens aides to babysitters, he wrote.

In an amicus brief, dozens of members of Congress argued that the field had changed dramatically since 1974, and that home-care aides should be covered under the FLSA.

“The home-care labor force is not what it was in 1974,” the brief said. “The entire enterprise has changed into a professionalized workforce that is exactly the type Congress intended that FLSA cover.”

Lynne Sladky/AP

If home-care workers were treated as professionals, rather than “elder sitters,” some advocates argue, receiving better pay and benefits and stable hours, it would be easier to attract workers to the field and to retain them. In addition, a nationwide training system could also help prepare workers for the challenges of helping the sick and infirm, which would also reduce turnover.

“Turnover is related to a lack of training as well as a lack of career advancement opportunities,” said Leanne Winchester, the project director for Direct Care Workforce Development, a program being run by UMass Medical School and the state of Massachusetts.

Though some states have training requirements, there is currently no federal standard for training or assessment of personal-care aides, which is an entry-level position in the field. Some states, including California and Iowa, have no training requirements at all. Many workers become personal care aides because they need a job and because someone—like my grandmother—is desperate for help, right away. They find the job on Craigslist and it seems like an easy way to make money, and then they run into obstacles—they’re not prepared to work with someone who has had a stroke, or to be in an environment that might have bed bugs— and they quit, said Lisa Gurgone, the executive director of the Home Care Aide Council.

Gurgone and others are advocating for more training for workers, which will prepare them for working in the field. As part of the Affordable Care Act, six states have piloted programs to train and evaluate the direct care workforce. Some of those programs, including the one in Massachusetts, included what's called a "career lattice," which allows workers to move laterally along a career path by developing specialized skill sets. The goal is that by acquiring different skill sets, they can then move up the career ladder into higher-paying jobs.

This was the first recommendation agreed upon by the Commission on Long-Term Care, which was tasked with coming up with recommendations as to how to best provide and pay for long-term care.

"Direct care worker positions are often viewed as low-wage, entry-level jobs with little to no opportunity for advancement," the Commission's report to Congress says. "Establishing career ladders and lattices can increase the desirability of these positions, and improve job retention."

I took a look at what this training might look like when I stopped by a class in Lynn, Massachusetts, for home-health aides, being run by All Care VNA and Hospice. All Care had posted ads on Craigslist saying it would train workers and then find them jobs, and many of the people in the room had come from other fields, eager to join a fast-growing profession.

“It’s a field that’s just going to keep growing and growing,” one student, Stephanie Rodriguez, told me. Rodriguez had previously worked in fast food and as a receptionist, but said she thought being a home-care aide would give her more flexibility to spend time with her family.

She sat at a long table with a dozen other students, all of whom were minorities. They had binders out and were taking notes when I walked in, watching a video that talked about proper techniques for bathing elders. The previous day, they’d gone over nutrition and planned some meals for would-be clients. Conversation had veered to cleanliness in seniors’ homes, and they learned to keep all their personal belongings in their car to avoid bed bugs, and to wear booties if there was a risk of infection. Later in the week, they’d practice “transfers”—helping seniors out of their wheelchairs and into bed or onto the toilet.

The training was based on the PHCAST curriculum, and seemed much more extensive than any of the quick babysitting prep talks I’ve ever heard, and I couldn’t help but wonder how people would fare in the field without getting this sort of instruction first.

Gurgone told me the training is useful in weeding out people who just want quick money but who won’t be reliable. One student who was going through the training learned about the possibility of a client having bed bugs, and quit then and there.

“These workers, they need jobs,” Gurgone told me. “But the people who succeed in this job, they do it because it's like a calling.”

Tony Dejak/AP

Many of the students in the room said they were testing out the field, and if they liked it, they'd perhaps trying to become nursing assistants or go to school for other jobs in the healthcare field. It was what drew some of them from other fields: After all, there are many low-wage jobs out there, but most workers won't find opportunities for promotion and further schooling in fast food restaurants.

Rodner Chery, for example, had worked in the kitchen of a nursing home for a decade, but wanted to do something different, he said.

“When you're working in the kitchen, especially if you don’t want to be there, you're stuck and you don't want to be,” he said. “Here, they let me do something different, and I can grow. I know the field is huge.”

No matter how much training workers receive, though, it’s unlikely that they’re going to stay on the job unless they can afford to do so. For this to change, states need to put more money into Medicaid, said Marquand, of PHI. But the opposite is currently happening. States including Connecticut, California and Illinois are planning to cut back on eligibility of Medicaid recipients and are requiring low-income seniors to pay more for their care as a way to close budget gaps.

Workers won't likely get help from their employers either: It was the associations representing home-care agencies that filed the lawsuit against the Department of Labor asking that workers not receive minimum wage or overtime.

Had the Department of Labor rule gone into effect January 1st of this year, as scheduled, "it will have a destabilizing impact on the entire home care industry," argued the plaintiffs, Home Care Association of America, the International Franchise Association and National Association for Home Care and Hospice (PHI argues that the $100 billion industry can afford to pay its workers a little more).

Some workers have unionized in an effort to force change in the field. This often begins with states recognizing independent home-care workers funded by Medicaid as public employees, which allows them to organize, as happened in Oregon, California and Washington. Home-care associations in Pennsylvania are battling an executive order by newly elected Gov. Tom Wolf that could make it easier for home-care workers to unionize. Lawmakers in Minnesota passed a bill last year allowing these independent home-care workers to be represented by unions, as did lawmakers in Connecticut in 2012 . After Vermont passed a similar bill, home-care workers there unionized too, as I wrote about this fall.

There is some proof that unionizing can raise standards: Ten years after Illinois approved a union for home healthcare workers, wages doubled and training and standards improved, according to NPR. The Vermont workers I talked to mentioned time and the significance of being in a union. Their jobs are isolating and stressful, but having others to talk to and advocate with has made a difference, they said. What's more, as union members, they are able to advocate for their clients, protesting against cuts in state Medicaid payments and services.

"For a long time, we were just employees of someone—an agency, the state," one worker, Amanda Sheppard, told me. "Now, we are being advocates and liaisons for our clients in the state."

Of course, depending on unionization to improve life for home-care workers isn't an easy fix, either. Last year, the Supreme Court ruled that home-care workers in Illinois cannot be required to pay unions fees if they're not in a union, categorizing the workers as "quasi-public employees"—not "babysitters," but not what advocates for home-care workers had wanted, either.

Read the article here:

http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/04/who-will-care-for-americas-seniors/391415/

About the Author

ALANA SEMUELS is a staff writer at The Atlantic. She was previously a national correspondent for the Los Angeles Times.

Follow her on Twitter

New Partnerships!

New Partnerships!

March 2, 2015

We are happy to announce three new partnerships this month. We would like to welcome Lakeline Personal Care Home, Hidden Hills Assisted Living and Memory Care and A Cedar Park Personal Care Home. We are looking forward to working with you. Please contact us directly for more information about the these facilities.

National Social Worker Month

National Social Worker Month

March 1, 2015

March is national Social Worker month. A big thank you to all the social workers in our industry that put in the effort to make our clients and their families lives better.

Now Offering Geriatric Case Management

Now Offering Geriatric Case Management

November 17, 2010

Texas Family Services is a FREE Senior housing locator! Our mission is to help you find the best Austin senior living care for your situation. We have the comprehensive information that you need in order to make a decision regarding which type of senior living care is the right one for you or your family member or loved one.

We also offer Geriatric Case Management services. For more information please call us at 512-574-1722.

Texas Family Services is committed to seeing seniors and families all the way through the housing and care management process. By linking them with the necessary services and support needed in ensuring quality care is given and remain in place. Either through social outlets, government programs or legal documents such as advanced directives.

Partnerships

Partnerships

January 14, 2010

Texas Family Services is pleased to announce that we have over 55 partnerships around Austin and the surrounding areas. We are always looking to build partnerships so we can better serve Seniors and their families! If you are not already partnered with Texas Family Services please contact us.

Follow Us!